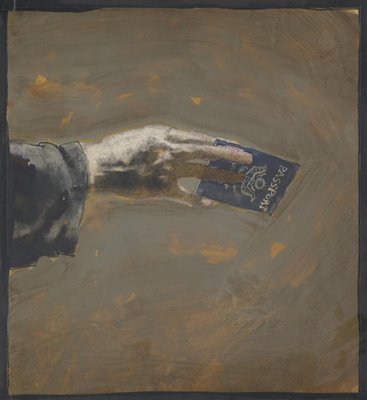

I love these powerful pictures by Kent Williams, one of my favorite artists working in graphic novels today. These kinds of images have their roots all the way back in the urschleim.

Williams is also a magazine illustrator, a gallery painter and an art teacher. He teaches contemporary figurative painting in Pasadena, California.

Some of his pictures are more successful than others, but Williams is one of the very few sequential artists who I think makes effective use of the technical tools and creative choices now offered by graphic novels. For example, the following panel from the graphic novel Tell Me Dark displays far more nuanced color and shading than was possible in previous generations of comic books.

As another example, Williams used a kneaded eraser to mold a figure by lifting highlights from a background of vine charcoal. This delicate technique was not possible with the printing technology for earlier comic books.

As another example, Williams used a kneaded eraser to mold a figure by lifting highlights from a background of vine charcoal. This delicate technique was not possible with the printing technology for earlier comic books.

The golden age of illustration began in the late 19th century as a result of the invention of photoengraving. Prior to that time, art could only be published in a book or magazine by painstakingly tracing the original image onto a wooden block which was then carved by hand by an engraver. The artist was at the mercy of the engraver (who often co-signed the finished block) as well as the printer. Photoengraving inspired a mini-renaissance because for the first time, books and magazines faithfully captured the artist's true talent (for better or worse).

Comics have now gone through a similar renaissance. For most of their history, comics were drawn in pencil by one artist, then traced in ink by a second artist for reproduction. Often, a third artist applied color on a separate page or guide sheet as a reference tool for the printer. Now graphic novels have overcome all these limitations of the medium. Today's artists are free to work with delicate line, or subtle gradations in color and value, or mixed media.

While many writers have taken advantage of the freedom of the graphic novel, very few artists have risen to the challenge. Most sequential artists treat the graphic novel like a super sized comic book on glossy paper. Even successful painters such as Alex Ross, who use the new image quality to convey slick, photo-realistic art, don't add much artistic integrity. Their art may be dazzling but it seems thin and lacking in humanity.

Apart from Williams, there seems to be only a handful of artists-- McKean, Miller, and perhaps half a dozen others-- who are doing artwork worthy of the medium.

Apart from Williams, there seems to be only a handful of artists-- McKean, Miller, and perhaps half a dozen others-- who are doing artwork worthy of the medium.