Cornwell has drawn thousands of hands in thousands of pictures, yet look how hard he still works to get the facts right:

The information in this drawing is different from the type of information that could be collected by a camera. Here is where Cornwell starts to select and digest certain facts to assimiliate them in his own personal style. Here is where he finds the contours of his future design. Here is where he establishes priorities.

Fritz Eichenberg once said, "what makes an artist create in his own particular style is an indefinable gift, almost a state of grace."

Maybe so, but I especially like preliminary sketches where you can see honest artists put that "state of grace" to practical use constructing a picture the way a carpenter might use tools to build a house. I love the candor and unpretentiousness of working drawings. Here is a nice selection by some extremely talented artists:

Frank Frazetta tries out two different positions for the leg of this rider. Yet, his attention always seems to stray back to the same thing...

In the final version of this image, Bernie Fuchs' lines will seem very spontaneus and natural. But here you see him explore, at a slower pace, how the width and variety of lines might work out.

Here, William A. Smith was not content with the break in the crease on that pants leg, so he went back and did it again. Below, we see him going back with white paint to reshape the lights and shadows in a dynamic fight scene.

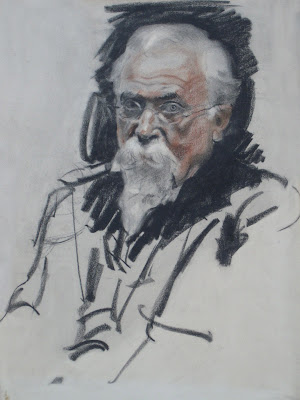

This is a preliminary study by Oberhardt for an ad for Fatima cigarettes. Despite the briskness of the drawing, he manages to capture a surprising amount of the subtlety of the form. But he is clearly not collecting information the way Cornwell was (note the difference in the treatment of the hand). Instead, Oberhardt's primary interest is in the overall shape of the lights and darks.

Like many artists, Oberhardt apparently continued to work on images in the back of his mind even while he was reading the newspaper.

This concept sketch by Rockwell may be tiny, but he meticulously plans all of the ingredients of a Post cover, including his signature and the trademark Post bars.

I love the vigor of this sketch of Katie Couric by Thomas Fluharty. It may seem as if he drew it at 90 miles an hour, but look at how he slammed on the brakes to capture the information he wanted about those teeth.

Another terrific example from Fluharty, cut and pasted with no pretensions. Look at the bold use of that soft charcoal to take chances with the shape of Obama's cheeks or ears. Yet, observe how he came back with a computer to test color and add such insightful expression to those eyes.

There are many interesting stopping points on the road to a completed picture. In recent posts, we have spent a lot of time discussing critics, curators and gallery owners who project their fanciful notions of what the artist had in mind. As far as I am concerned, the most reliable way to discern the inner thoughts of an artist is to spend some time with the working drawings that led up to the final product.